A POST FROM Emmanuel Jal’s Facebook page dated Thur 27 Jul 2023:

Do you know I have a book out called warchild?

I use to nose blood every time I did a deep interview with writer and nightmares for a couple of months. When the book was done I felt so light and relieve from so much cabbages in me.

View original:

https://www.facebook.com/EmmanuelJal/posts/pfbid02xR2VczXGoYNbqtSHoSPFG4qQo9d6CYdbhwYE4bEocknMCZZ6bHzdJL3TEcoHHtctl

[Ends]

___________________________________

NOTE from Sudan Watch Editor: Here is a review and excerpt posted at Amazon.com in 2009.

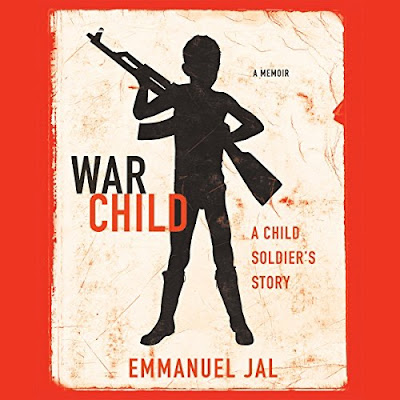

War Child: A Child Soldier's Story Hardcover – February 3, 2009

By Emmanuel Jal (Author), Megan Lloyd Davies (Contributor)

In the mid-1980s, Emmanuel Jal was a seven year old Sudanese boy, living in a small village with his parents, aunts, uncles, and siblings. But as Sudan’s civil war moved closer—with the Islamic government seizing tribal lands for water, oil, and other resources—Jal’s family moved again and again, seeking peace.

Then, on one terrible day, Jal was separated from his mother, and later learned she had been killed; his father Simon rose to become a powerful commander in the Christian Sudanese Liberation Army, fighting for the freedom of Sudan.

Soon, Jal was conscripted into that army, one of 10,000 child soldiers, and fought through two separate civil wars over nearly a decade.

But, remarkably, Jal survived, and his life began to change when he was adopted by a British aid worker.

He began the journey that would lead him to change his name and to music: recording and releasing his own album, which produced the number one hip-hop single in Kenya, and from there went on to perform with Moby, Bono, Peter Gabriel, and other international music stars.

Shocking, inspiring, and finally hopeful, War Child is a memoir by a unique young man, who is determined to tell his story and in so doing bring peace to his homeland.

Excerpt

THE VILLAGERS’ VOICES rose louder and louder as they sang. Drums thudded to greet us: the family of Simon Jok, the SPLA commander who protected this village and the ones around it. Everyone seemed so happy and I was too as I stood next to Babba—taller than I remembered, with a bigger belly now. He’d been treated like a king after arriving earlier in the day, and he had shown us to the tukul we’d been given as a home. We even had cows now, just as Mamma had said we would. They were black- and- white with big, curled horns. An elder, naked except for beads around his waist and a necklace of ostrich eggs around his neck, stood in front of my family. Next to him was a riek—the altar found in every home to make sacrifices to gods. Like many in the south, these villagers were animists who believed in many gods and made sure a cow’s blood touched the riek whenever one was slaughtered to please them. The singing got louder as an old woman tried to sprinkle water on us.

“Please no, we are Christian, Mamma said.

“Jeeeeesus,” the woman crooned as she carried on sprinkling water. A bull tied with a leather rope stood in front of the riek. Its eyes rolled as the old man took a spear and stood in front of it. It knew what was going to happen as well as I did and moved restlessly. The elder lifted his spear and in one fast move sliced into the bull’s heart. I watched as it fell on its left side and blood spread slowly across the earth. It was a blessing. Later the elder would cut off the bull’s head and skin before handing me one of the testicles. It was burned on the fire and I had to eat it, but while the village boys loved the taste, I did not.

“Come, Jal,” my father said after we had finished.

We left Mamma, my sisters, and my brothers behind as we started walking through the village with some soldiers. They were big and strong too, but I knew my father was the most important one. He had just come from Ethiopia, where he’d learned to be a lieutenant commander. “I am happy you are here where I can visit you,” Babba said as we walked.

So was I. It had taken so long to escape Bantiu. We’d had to turn back that day on death route because a village was burning in the distance, and after that it was always the same until Mamma made a new plan. The only people the troops sometimes allowed to move in and out of the town were villagers from outside Bantiu who came in to sell milk to the soldiers. It was dangerous but Mamma told us we were going to pretend to be with them. I thought of the naked children and women who wore just a skin around their middle. I didn’t want to be bare. But of course I had no choice, and soon Mamma, Aunt Nyagai, Nyakouth, Nyaruach, Miri, Marna, and I had melted into a group.

My brothers, sisters, and I hated being without clothes and shoes, and Mamma looked strange too. The sun was so hot as we walked that the earth burned us and we had to take turns standing on her feet. The moment our turn came to an end, we’d step back onto the ground, and thorns would dig into our soft skin as the village children laughed. I turned my back on them. All I cared was that I was leaving Bantiu—and the war—behind. I looked up now at Babba as he spoke to me.

“This is our land,” he said as he swung his arm in the air around him.

“This is what we are fighting to protect because this is what the Arabs are trying to take from us.

“They want to change us, our way of life, and make us like them. But I will never let them do that.”

Bending down, Babba put his arms around mine and lifted me into the air. Higher and higher I went until I could finally twist my legs around his shoulders. I felt his hands holding firmly on to my legs as he stopped to speak to a man.

“This is my son,” Babba said as I sat silently looking down.

I knew he would never let me fall.

Babba left soon after to go back to the war, and I cried when he told me he was going. He saw my tears and told me I was a man, a soldier, a warrior now.

The village was as beautiful as I’d been told so long ago it would be. Tukuls lay in long lines near ours, and there were also bigger luaks, where the men slept with cows after the fire- red sun had sunk into the night. The villagers also had many sheep and goats, and the thing I liked most was that I could walk wherever I liked because it was safe. Soon I had learned not to wear clothes as I made friends with some of the village children who I entertained with stories of the city. I liked making them laugh as I told them about the black- and- white television we’d had—they didn’t understand that a box could show moving pictures. But there were also many things for me to learn. Village life in Sudan is traditional, and girls and boys have different jobs to do. While Nyakouth was taught how to help in the kitchen and milk the cows, I learned how to dry dung, which was then burned on fires to chase mosquitoes away. Nyaruach tried to help us, but she mostly made more trouble than she solved. Her name meant “talkative,” and she loved the sound of her voice even more than I did my own. Somehow Mamma always found out whenever I did anything wrong, and I was sure it was because of Nyaruach and her big mouth. I was glad that Nyakouth was quieter.

Miri and Marna were still too young to work, and we, the older children,

helped look after them. Of course, there was still time to play, and the game I liked most was with a baby sheep I had made friends with. Staring at it seriously, I would drop to my knees and throw myself forward as it butted its head against mine.

“You will break your bones one day,” Nyakouth used to scold me when she heard the crack of our heads colliding.

I didn’t listen because the sheep made me laugh too much to stop.

Mamma was also busy. As well as feeding Miri and Marna her milk, she looked after the many people who arrived to see her. Injured soldiers came who needed their wounds dressed with old pieces of bedsheets, and Mamma also had some needles, which she boiled again and again, to look after them.

Villagers also arrived at our tukul—some wanting the fruit of the neem tree, which Mamma boiled to treat malaria, while others asked for the salt- and- sugar drink she made for those weak with diarrhea. Although the war was far from us now, we still had to learn to follow rules. Soon after we arrived, Mamma was beaten with a stick by angry SPLA soldiers. Villagers were supposed to leave out food and milk to feed the rebels, and she hadn’t known. What they didn’t realize was that when government soldiers came to watch the bush with binoculars, the villagers also gave them milk. But Mamma quickly learned what she had to do, and Babba sent us a soldier called Gatluak to look after us so we were safe again.

I loved life in the village. Watching the ostriches and buffalo in the bush, learning to use the ashes of cow dung and sticks to brush my teeth, and dyeing my hair red using the bark of the luor tree. I also liked having Gatluak with us because he played with me often. But most of all I was glad to have left the war behind.

On a clear morning, we were all outside. Nyakouth was milking a cow and I was bringing the others outside so I could sweep up the dung in the luak. But really I just wanted to keep laughing at what I’d seen earlier. There is an animal in Sudan called a jeer, which is about the size of a large cat. Earlier one had come out of the bush and fallen asleep in the grass near our house—or so we’d thought. The jeer lay still as the minutes passed and flies collected on its huge bottom. But a passing chicken could not resist such good pickings and pecked along the trail of flies until it reached the jeer’s backside. As its beak pecked, the jeer woke up, sucked the chicken’s head inside, and ran away. Nyakouth and I had laughed and laughed as we watched. Now I giggled to myself again as I led a cow out of the luak into the daylight. I hoped that we would see another jeer soon.

I froze as I saw an Arab standing in front of me. He was wearing a long, black jellabiya and holding a gun. Everyone had stopped moving. The morning was silent. The Arab said nothing as he walked toward the tukul and came out with Gatluak.

“Put your hands up,” the Arab shouted as he pressed his gun into Gatluak’s back. “Turn around, move over there.”

Gatluak stepped forward and lowered his hands as he turned around to face the Arab. The two men stared at each other for a second before the sharp crack of bullets sliced open the silence. Gatluak dropped onto the ground and the Arab started running away. My eyes did not follow him. All I could do was stare at Gatluak as he lay on the ground. I knew the sound of a gun well and how people looked after they’d been shot, but had never seen the moment when bullet met flesh.

I couldn’t breathe. Gatluak’s stomach had been ripped apart and his intestines spilled out of the wound. The smell of shit filled the air. Steam rose from his body as he lay on the ground, body jerking and eyes empty. I watched as Mamma sank to her knees beside him. Tears ran down her face as her hands closed around Gatluak’s stomach. They were bright with blood as she tried to hold the skin together.

“Get some rags,” she shouted.

I couldn’t move, couldn’t take my eyes away from the sight of Gatluak’s guts—gray like a goat’s—mixing with a sea of red. I watched as he twisted in the dirt, his breath coming in gasps as he choked for air. Then a low moan escaped his lips and he went silent. Mamma bent her head toward him and cried. Still I did not move.

Days later a witch doctor arrived at our home wearing a leopard skin and carrying a big spear. He was tall and wore many beads and bangles, which rattled as he told Mamma he wanted us to sacrifice a black goat for his gods so that he could tell us our future.

“He is a devil trying to trap us,” Mamma said as we stared at him. “We will not give him a sacrifice.”

But the man didn’t listen as he started banging a drum in front of our tukul.

“You will be punished,” he said in a suddenly deep voice. “Our god is the one who protects you, and you must listen to him. He is telling me that your village will be burned. You must listen. You will soon all die.”

“Leave us in Jesus’ name!” Mamma shrieked at him.

Soon he left, but the fear that had wrapped itself inside my stomach the day Gatluak died now pulled even tighter. I knew I shouldn’t listen to a man who worshipped gods that were not ours, but I couldn’t forget his words. I wondered what it all meant for us.

It was afternoon and I had left the village with my friend Biel to go fishing. We were walking back home when we heard the deep blast of a big bomb. It was close. We looked at each other quickly before running to the top of a slope. Below us was our village. There was smoke and fire, people running in different directions like frightened chickens. Government soldiers were attacking.

The savanna grass crunched beneath our feet as we started running down the hill. As we neared the road into the village, we saw two SPLA soldiers lying on the ground ahead and stopped. Hiding ourselves in the long grass, we poked our heads high enough to see about twenty villagers gathered by the side of the road surrounded by soldiers pointing guns at them. Other troops were beating a family.

“You’re keeping rebels here, aren’t you?” they screamed. “You’re giving them food.”

Children cried as they watched while the rest of the crowd—men and women, babies strapped to their mothers’ backs, and elders—looked on with fear in their eyes.

“We’ve found these rebels here,” a soldier shouted as he pointed to the dead SPLA. “Where are the others? Where are the rest of your men?”

Suddenly the soldiers rushed at the people and started pushing them with their guns toward a luak nearby. The villagers cried as they were herded back, and a man ran toward a soldier. A bullet rang out, then he dropped to the ground.

“Get inside,” the soldier hissed as he fired at two other men in the crowd.

Beside me Biel was breathing hard. I looked at him. Tears were on his face. I turned my head again to see troops hitting women with their guns as they pushed the villagers inside the luak. Bullets cracked in the distance and screams echoed above us as the soldiers closed the wooden door. I could hear people crying, and I thought of them trapped in the darkness as I watched a soldier throw gasoline from a can onto the luak’s straw roof. I saw the light before I heard the noise. Something bright burned in front of my eyes, and a huge boom roared in my chest as the luak exploded into flames. Biel jumped up and started running toward the flames. I knew I should not follow. Death was trying to trap me in his jaws once again, and I had to move faster than him. I turned and started running back into the savanna. Deeper and deeper I went into the long grass as my heart pounded in my mouth. My stomach felt liquid. I wanted to empty myself. Suddenly a hand closed around my neck and I screamed as it pulled me to the ground. I saw a man’s face. I was dead.

“Don’t move,” a voice said. “You must stay with us, keep hidden.”

Looking around, I saw a small group of villagers. They were trying to escape death too. I turned onto my stomach as bitter smoke filled my lungs and sounds washed over me—screams and the k-k- k-k- k-k- k of gunfire. Where was Mamma? Where were Nyagai, my brothers and sisters? When would Babba arrive to save the village?

I don’t know how long it was before I felt the man’s hand take hold of me once again and pull me to my feet. We started walking through the grass and soon reached the river, which we crossed before making our way to another village where Mamma found me.

“We should have listened to the witch doctor,” I said to her.

I couldn’t stop thinking about the people in the luak. I could see their faces, the hate in the soldiers’ eyes as they looked at them.

“Are they dead, Mamma? Have they gone to heaven?”

“Hush, makuath,” she replied. “They are sleeping, and if they are in heaven now, they are safe. All the pain they have suffered will have ended, their bodies will be whole again. God is watching over all of us and He will look after them.”

“But when will we go to heaven?”

“I cannot tell you, Jal. Only God knows when each of us will join Him.” I looked up at Mamma. I hadn’t known before that the people I saw were just asleep. I felt happier now.

Pain returned to our lives once again. Our village had been burned to the ground and we couldn’t return. Many others did, though, and I soon learned that people go back to the place of their birth just as birds return to their nests. Even if nothing was left, they would still go back and rebuild on the place their ancestors knew. Mamma, Aunt Nyagai, my brothers, sisters, and I had no such place, and we ran and ran as village after village was attacked.

People were generous with what little they had, and we were given a place to rest and food to eat as we moved across the south with other refugees.

“God will protect us,” Mamma told us night after night, and cuddled us to her.

But even she was different now—her smell had changed. In the city the scent of perfume and incense had clung to her skin, whereas now the smell of milk mixed with the sharpness of fear lingered on her.

I knew why. The soldiers came in jeeps and trucks to attack, or sometimes we would hear tanks in the distance and escape the low growl. But on other days they arrived as light was breaking and took us by surprise. The dry season was the worst because they could move more easily. Burning and looting crops, they destroyed anything that might feed us or the SPLA. They wanted us to starve and set village after village afire as the lucky ones escaped to the rivers or the forest, while their friends and family perished.

Murahaleen also came, and they were the ones I was most afraid of as they shouted, “Allahu Akbar,” and shot. The village men would try to fight them with spears, but they were no match against the guns, and the murahaleen would kill everyone they could.

I remember walking into one village where bones covered the ground. Some were small and some were large, and Mamma couldn’t cover our eyes that day—there was too much to see. Tears ran down people’s faces as they cried without sound, and I had many bad dreams afterward.

Sometimes Mamma would sing me a song to go back to sleep, but the only time I felt really protected was lying beside her or Nyagai. I had to make room for the younger children, though, so I never really did feel safe.

Sometimes we saw helicopters in the distance—gunships that hovered in the air before firing—and I learned that people running for their lives never go in one direction. Instead they scatter like ants and flee wherever instinct takes them. With the smell of burning flesh in the air and the memories of bodies lying still on the ground, I’d run as if the dev il were chasing me. I became good at war. Soon I knew the different sounds of explosions—the boom of big bombs, the smaller one of grenades thrown from the hands of soldiers, the hiss of a rocket from an RPG. There were also different guns—the AK- 47s carried by the SPLA, the Mack 4s the murahaleen used, and the G3s of the government soldiers. I learned how to run until I felt my feet would touch the back of my head even as my stomach twisted and tumbled inside me. Often I fell down and each time prayed that I would disappear into the ground. But of course I had to get up and start running again. I wondered if I would ever stop.

Stories woven tight with threads become simple ones in the mind of a child, and the war in Sudan was less distinct than a fight between black and Arab, Christian and Muslim. Centuries of marriage had blurred our tribes, age- old rivalries were used by the northern government to pit one against the other, and black Muslims from Darfur fought alongside Arab Muslim troops in the belief that they were taking part in a holy war against the infidels from the south. Even black African Christians joined the government forces to earn money.

But I forgot about the African faces I saw among the enemy as I thought of the Arabs who attacked us and my hate grew inside. Arabs and murahaleen became one in my mind—jallabas—whom I hated more and more.

In the north I’d wondered why they had better clothes than we did, why they were allowed to go to mosques while Mamma got beaten for going to a church. But now I saw for myself what they could do. The answer was always the same when anyone asked who’d done something: “Jallabas—Arabs.” The jallabas were to blame for all I had seen; they were the reason my family had been tossed onto the wind as our world disappeared. “I don’t like them,” I’d tell Mamma. “They should go to hell. They are bad people.”

“No,” she would reply. “Heaven is for everyone and God is for all people.”

Sometimes I wondered how God could let them into heaven when they killed everyone, and secretly I told myself I would attack the Arabs with my father when I grew up. All I wanted to do was stop them from hurting us anymore.

But at times I could forget the hatred I felt for jallabas because children are better at war than adults. The moment the battle was behind us, we would start playing again and laugh as we remembered how funny people looked as they ran. It was only at night that you couldn’t forget, but in the day we would always find a game to play in the dust or a joke to tell. My family and I were separated many times as war snaked around us.

Sometimes I was alone, sometimes with Aunt Nyagai or Nyakouth, but I quickly realized that wherever I found myself, I had only to mention my father’s name and Mamma would find me. I hated being apart from her, and in the days without her I would be restless and crying as I waited. Yet even when Mamma came back, I would be ready to run again, and if we ever came to a stop in one place, I would feel my stomach trembling as it waited for the next battle.

“We are safe now,” Mamma would tell us.

But the war was never far away, and even when we did stop, people were forced to help the SPLA on the front lines by carry ing food and ammunition there. Aunt Nyagai had to go once and was silent when she returned. She’d seen many dead people and heard of families crying for boys who’d been taken as slaves on sugar plantations and girls who would be used by the militiamen for kunkebom. She refused to eat when she came back and couldn’t taste meat. I knew what she was remembering— the smell of the burned people.

“It was so terrible,” I heard her say one night to Mamma.

I’d been woken up by the sound of Aunt Nyagai being sick, and now she spoke to my mother in a low voice.

“Angelina, there were children and babies, a pregnant woman lying burned on the ground with her child inside her.”

“Hush, Nyagai,” Mamma said. “You’re safe now.”

I was scared by what I’d heard. It put pictures in my mind—I could smell the air and hear the cries. I kept telling myself what Mamma had told me—the people were asleep and would wake up later, and if they didn’t, then God would make them whole again in heaven. It felt as if we’d been running forever until we finally found a village that wasn’t attacked for many weeks.

“The SPLA are protecting us now,” Mamma told us one night. “The war is distant. We can stay here and rest.”

I almost dared to believe her. Babba had brought us some cows, his soldiers had built us a tukul, and Mamma’s belly had swollen with another brother or sister for me.

“Tell us a story,” Nyaruach said.

“Will you ever be happy to listen to the silence?” Mamma laughed as she sat down beside us. “I will tell you one story and then you must sleep.”

We looked at her as she sat down.

“Did you know that the fox and the dog were once cousins who played happily together?” she asked. “But one day the dog went to visit the fox and told him, ‘It is hard to live in the bush, but in the village all you have to do is warn people when the hyena is coming. You should come and live with me.’

“So the fox decided to go to the village, but got there to find the dog hadn’t been given any food that night. Silently he watched as the dog went to his master’s house to ask. But he was kicked and given only bones to chew on.

“The fox told him, ‘In the village you are humiliated. All you get is bones. In the bush I kill my own meat and eat what I want.’

“ ‘Just wait and see,’ the dog told the fox. ‘My master looks after me well.’

“And so the fox stayed, but the next day the dog and the fox killed an animal, took it to the master, and were given only bones to eat once again. “ ‘I must go back to the bush,’ the fox told the dog. ‘I will never be happy here.’

“And so the fox returned to the bush and the dog stayed loyal to his master, and the two became enemies, which is why they fight today.”

Mamma kissed the younger children as I turned onto my side to sleep. I was seven—too old for kisses. I felt her hand touch my shoulder as I closed my eyes.

The boom in my belly told me that war had come again. I opened my eyes. I could hear guns spitting bullets and the low tuk- tuk- tuk of helicopters throbbing overhead. I jumped to my feet. Everyone else was up. Miri was crying, scared by the loud noises. Running to the door of the tukul, we plunged into the daylight. My heart was beating and my legs felt weak. Would I be able to run fast enough this time? Aunt Nyagai’s hand took mine as Mamma held on to the babies and we all started running. All around us people were screaming. Dust and smoke filled the air; I could smell fire.

“Wait,” Mamma shouted as she turned toward the tukul.

I knew what she wanted—her medical box. It was the one thing she always ran with during war.

“Don’t go,” Nyagai screamed. “There’s no time.”

Mamma stopped for a moment, unsure of what to do. She turned toward us again. “Run for the river,” she screamed.

I could see government soldiers in the distance and told my legs they must be strong as I gripped Nyagai’s hand. I didn’t look behind at Mamma and the others. I knew they were there.

Suddenly the little boom of an exploding grenade came from near us and I heard cries.

“Quick,” Nyagai screamed, and we turned toward the forest that lay on the outskirts of the village. We’d be safer among the trees there.

My feet flew through the air as I forced myself to go quicker. The battle screamed in my ears, and all I

could feel was Nyagai’s hand in mine.

Thorns dug deep into my legs but I didn’t feel them. Fear will always win against pain, and all I had to do was run. Run and run, keep going, never stop until I’d left the guns behind. I wanted to silence the crack and roar and hiss and screech of war forever.

When the world was finally quiet again, I realized that I had lost Nyagai.

I was alone but knew what to do. I joined a crowd of refugees to start walking. I didn’t know where they were going, just that when they finally stopped, Mamma would find me. She, my brothers, and my sisters had to be somewhere close by, and until I met them again, someone would look after me as always.

“Mamma will find you,” I told myself again and again. “God will look after her.”

View original: https://www.amazon.com/War-Child-Soldiers-Story/dp/0312383223

___________________________________

War Child: A Child Soldier's Story

Audible Audiobook – Unabridged

Emmanuel Jal (Author), Ademola Adeyemo (Narrator), Macmillan Audio (Publisher)

©2009 Emmanuel Jal and Megan Lloyd Davies (P)2009 Macmillan Audio

Listening Length

8 hours and 59 minutes

Author Emmanuel Jal

Narrator Ademola Adeyemo

Audible release date February 3, 2009

Language English

Publisher Macmillan Audio

ASIN B001RMWATO

Version Unabridged

Program Type Audiobook

Read & Listen

Switch between reading the Kindle book & listening to the Audible audiobook with Whispersync for Voice. Get the Audible audiobook for the reduced price of $7.49 after you buy the Kindle book.

View original: https://www.amazon.com/War-Child-Emmanuel-Jal-audiobook/dp/B001RMWATO/

[Ends]